House of

House of A Thousand Treasures

A Thousand Treasures

House of

House of

house is not a home until it is furnished. Well aware of this, the two sisters who provided the funds to begin construction on Alumnae House put out the call to fellow alumnae for help outfitting the new building. And help they did: Gifts large and small began pouring in, ranging from grand items to small necessities. This began a tradition of gifting items and funds to the House that continues to this day. In fact, the vast majority of furnishings and artwork that have graced Alumnae House over time have been donated or purchased by alums, not the College.

Alums donated trees and other plant materials for the grounds. They sent books they had written for the Alumnae House Library. Queen Ferry Coonley, one of the original benefactors, provided curtains and weaving for eight bedrooms.

Two silver vases and a dress belonging to Princess Ōyama (Sutematsu Yamakawa), class of 1892, were displayed in a room dedicated in her memory by the class. A watercolor of Matthew Vassar’s brewery, originally displayed in the pub, is a gift of Martha H. MacLeish, class of 1878; it was painted by her daughter, Ishbel, class of 1920. As part of the house’s 75th anniversary celebration in 1999, Martha Lingua-Wheless ’78 coordinated an Anniversary Quilt with over a dozen alums, which is still displayed on the second floor. And the list goes on!

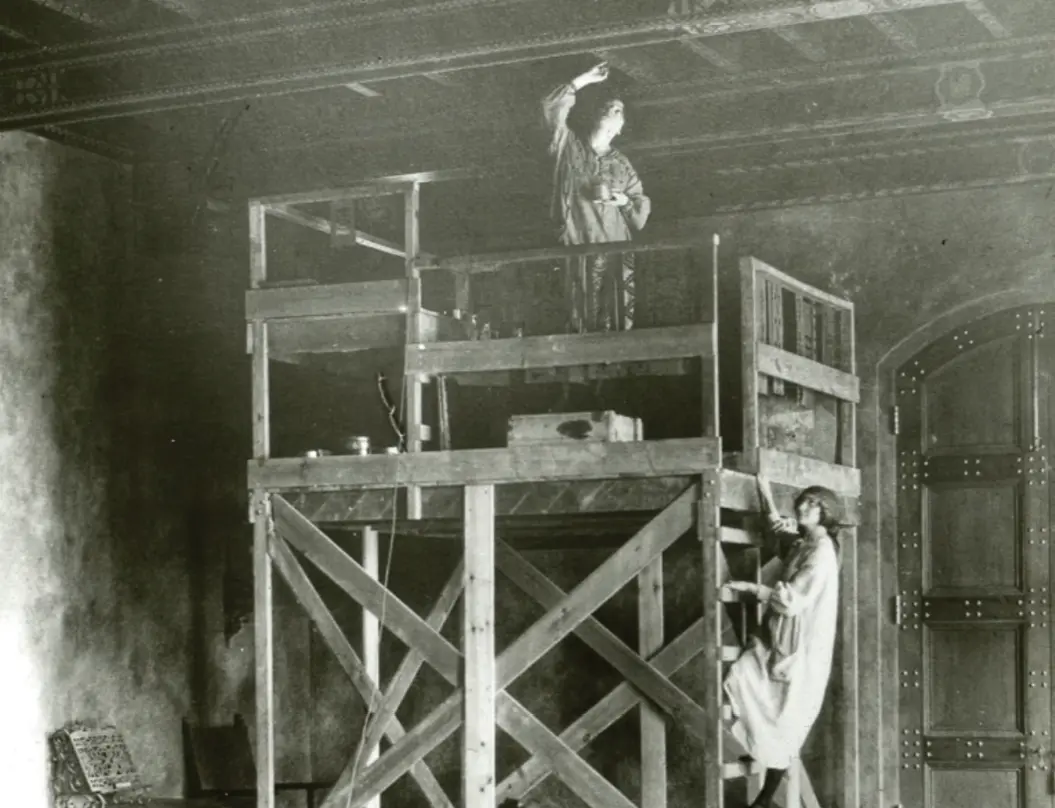

The most iconic gift to the House, of course, is The Great Wonder: A Vision of the Apocalypse by Violet Oakley, a triptych painted by an artist personally connected to Vassar that was unveiled amidst great fanfare at the house’s formal dedication on June 8, 1924.

The Great Wonder and Great Influence of Violet Oakley

In a pamphlet handed out at the dedication ceremony, Oakley explained the message of empowerment she wanted women to take from the artwork’s central image:

Oakley’s original furnishings can still be found throughout the house. However, much of it has been moved to other rooms, as successive house decorators prioritized creature comfort over artistic statement.

Pub Murals by Anne Cleveland

As they were being painted, Liz DeLong ’47 offered a perfect tongue-in-cheek description in the June 5, 1946, issue of the

Miscellany:

Restoration and Modernization

These gifts all help to maintain the feeling so many have when visiting: that Alumnae House truly is a home away from home.