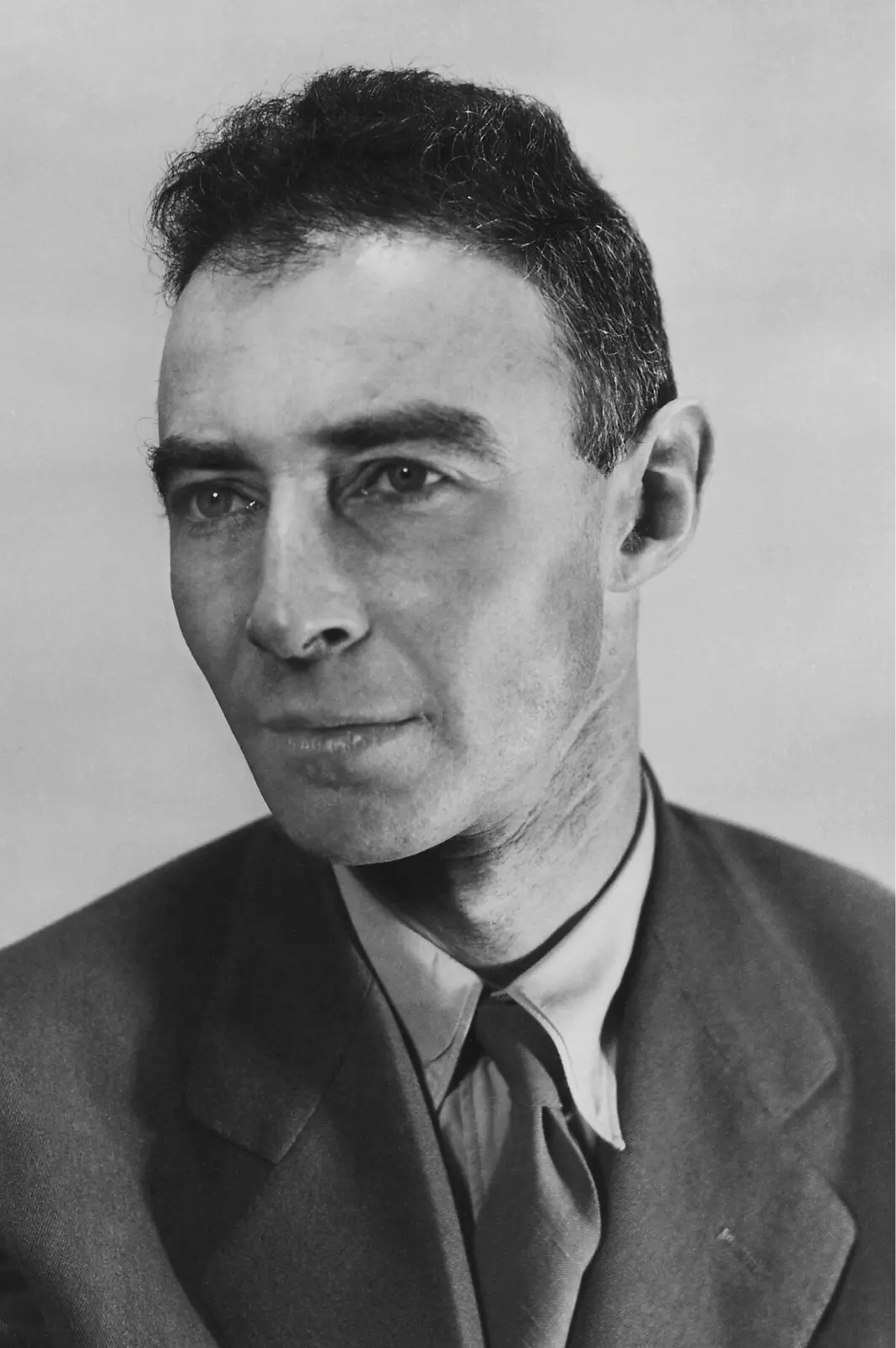

When Oppenheimer Came to Campus

In October 1958, about a decade and a half after leading the Los Alamos Laboratory in developing the atomic bomb as part of the Manhattan Project, Oppenheimer came to Vassar. Then the Director of the Institute for Advanced Study, he gave a speech in the Chapel and spent the next day visiting classes and meeting with students, faculty members, and science clubs. He also did an interview with The Miscellany News, telling the student newspaper that education was a “roadmap” to knowledge areas, but also that one should not take it too seriously because the roads are always being torn up.

U.S. Department of Energy

So when Oppenheimer arrived in Poughkeepsie, the Vassar community must have been eager to hear his thoughts. In his speech, “Knowledge and the Structure of Culture,” he focused on the expansion in human knowledge. “Today it can hardly be doubted that every 10 years or so we know twice as much as we did 10 years before,” he told the audience. Information did not go to everyone or to individuals, but instead to communities of specialists “who are in charge of that particular adventure,” he said. A person can’t know everything and instead must “ignore a great deal which, as an organism, we are perfectly capable of knowing,” he continued, “blotting out a great part of the truth in order that some truth may be perceived.”

He concluded by saying that in uncertain times, science provides order. “In this vast world, with its unceasing change and its immense novelty, without precedent, beyond easy comprehension,” he said, “there are present for us these beautiful, simple, always growing perspectives of order, more than ever before in man’s history.” He received a standing ovation.

Memories of the lecture would remain with students for decades. Katie Webb Johnson ’62, who was just weeks into her freshman year, didn’t know much about Oppenheimer ahead of the talk. “I remember being extremely impressed by him as a speaker,” she says. “But I was struggling to keep up because I was not well versed in those things.” She recalls others in the audience having stronger thoughts about the speaker, given the security-clearance controversy, which even the Misc. alluded to in the lead-up to the lecture. “There was a significant emotional aura, cloud, around his speech,” Johnson remembered—many students in the audience “had opinions.”

Off campus, alums debated the merits of inviting Oppenheimer, too. Writing to VQ, a 1928 alum questioned why Vassar would invite such a poor security risk. “Is loyalty to country in poor repute at Vassar these days?” she asked.

Associate Professor of Physics and Science, Technology, and Society José Perillán, who directs the STS program, has incorporated Oppenheimer’s lecture into a class. He typically has students analyze a 1959 essay by philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn, and this fall he added the Oppenheimer talk, “putting them into conversation,” he says. “It’s just a fascinating point/counterpoint of a historian of science who was trained as a scientist, and this great scientist, Oppenheimer, who’s reflecting on knowledge and the creation of knowledge and our modern scientific enterprise.”

Library of Congress

Tatlock arrived at Vassar after her father, a literary scholar and professor at another institution, had spoken on campus multiple times. As a student, her social justice concerns were in evidence. Writing for the Misc., Tatlock penned an eyewitness account of a labor strike, and made the local news when she and other students wrote a letter in support of people who were marching for food and shelter. A Poughkeepsie Eagle-News editorial said the letter “will doubtless start new comment about radicalism at Vassar.”

As this summer’s film depicts, Oppenheimer and Tatlock’s relationship was complex. They met through friends at Berkley the year after she graduated from Vassar (she was a graduate student and Oppenheimer was a physics professor). She is said to have introduced him to the Communist Party. He later testified that they almost married twice. He instead married Katherine “Kitty” Harrison in 1940, but he and Tatlock, who would go on to become a psychiatrist, continued to meet. They are last known to have seen each other in 1943, an encounter that alarmed U.S. intelligence due to concerns that Oppenheimer might use Tatlock to pass information to the Soviets.

The following year, Tatlock, who had battled depression throughout her life, was found dead by an apparent suicide, though Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin in their book American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer explored other theories, including assassination.

Oppenheimer addressed their relationship during his security hearing a decade later, telling the panel, “She loved this country and its people and its life.” What he didn’t say was that she may have had trouble being happy in her own.