Restorative Practices: Learning to Be in Community with Others

ore than a decade ago, Vassar had an incident that changed its approach to community care. In 2013, two Black students were in a residence hall laundry room going about their day when campus security officers approached them, wondering what they were doing there. Two other students had called Campus Safety, alleging they didn’t look like they “belonged” there. The young women quickly resolved the situation by showing their IDs, but the incident shocked and hurt them. How could their peers not see them as part of the same community?

They wanted to talk through the experience with the students who phoned Campus Safety. So, they approached Dean of Student Living and Wellness Luis Inoa, who, at the time, worked as an Assistant Dean of Students and the Director of Residential Life. The students requested a restorative circle.

The young Black women had encountered the idea of “circle work” in a class that discussed the Restorative Justice Movement. They had learned about the movement, which developed from Indigenous peacemaking circles and was brought into the Western lexicon in the 1970s as criminal justice advocates sought approaches outside of the prison system to address harm. Although modern uses of this approach initially grew out of the criminal justice movement, practitioners have found this approach also has applications in workplaces, schools, and universities alike. Scholars now study this movement as a transdisciplinary social science, cutting across disciplines like education, ethnic studies, and sociology, among other fields.

As a reconciliation technique, this process promotes mutual understanding, accountability, and community development rather than the traditional justice approach, which focuses on punishment and retribution. Within this framework, a circle mediation, theoretically, would help all of the students involved explain how they felt and hopefully heal from the experience.

Dean Inoa agreed and set up a meeting to try out this new technique. However, the meeting did not go as planned.

At that moment, Dean Inoa knew Residential Life needed to equip itself with the tools to better serve students in the future. Reflecting on that moment, Dean Inoa said, “This [restorative practice]work has always been in honor of those two young women.”

The summer following the incident, Dean Inoa worked with his colleagues to rewrite Residential Life’s mission statement and formed the Restorative Justice Ad Hoc Committee (RJC) to address issues of belonging that students didn’t want to bring to the student conduct office. As a part of their initial proposal, house teams, student fellows, and other related staff would be trained “to use proactive and reflective circles.”

Although this initiative had some successes, for these methods to take root throughout campus life, Dean Inoa knew that Vassar, as an institution, would need to invest in restorative practices. The opportunity for this kind of expansion came in 2023 as Vassar moved the Mellon-funded Engaged Pluralism initiative into a permanent university-wide program.

This structure is key to building a campus capable of navigating through conflict, says Kimberly Williams Brown, Director of Engaged Pluralism (EP) and Associate Professor of Education. She notes that college can be the first time a student encounters different cultures, values, and perspectives. And when people from different backgrounds must interact for the first time, disagreements naturally arise. In their home and grade-school environments, students might not have learned how to talk through these moments in ways that prioritize mutual understanding or maintaining community engagement.

The EP program seeks to build inclusion and belonging on campus through four tools: intergroup dialogue, storytelling, inclusive pedagogy, and restorative practices. The latter helps students develop the conflict resolution skills they need to engage in the other three.

Without this throughline, Williams Brown said, “it can be easy to only see the world from our perspective.” So, creating spaces for mistakes and empathy gives students the tools to stay invested in a community even when they feel uncomfortable.

“The EP space becomes that space where people can try things out, people can make mistakes, they can say the wrong words, but then you’re going to get a deeper understanding of why, in a contemporary context, a word may no longer be used,” Williams Brown noted. “One has to also be willing to learn, to sit with nuance.”

“The idea is to proactively support our student body in particular, but the entire campus by extension, in building their skills for encountering conflict, moving through it with resilience, and healing from hurt in a meaningful and connected way,” Munroe said. These skills are important on campus and also as the students encounter conflict outside of Vassar.

On the day-to-day, Munroe’s role takes many forms: group sessions, one-on-one meetings, leading workshops and trainings. She and her colleagues across the EP team—EP Director Williams Brown; Director of Inclusive Pedagogy Alexia Ferracuti; Associate Director of Organizational Development and Employment Equity Fresia Martinez Olivera; and program administrator Selena Hughes—develop programming where the Vassar community can engage across differences. The spring 2025 program series, “Exploring Difficult Dialogues,” explores various aspects of censorship and free speech. The series kicked off in February with a Q&A with Ian Rosenberg, a lawyer and the author of The Fight for Free Speech: Ten Cases That Define Our First Amendment Freedoms (NYU Press, 2021).

Munroe also manages eight student facilitators who act as RP ambassadors on campus and create student-led circles to discuss campus and societal issues. After a February presentation from the EP Race and Racism in Historical Collections Working Group focused on Vassar’s 1969 Black Studies Sit-In, student facilitators organized a workshop to debrief the presentation. Students created collages that explored what it means to be a student activist and how students can make a difference against injustice. This event and other restorative circles gave them a chance to process difficult topics in an encouraging and collaborative environment.

Munroe supports the student fellows in the Office of Residential Life, as they use circle processes and other community-building tactics across residence halls. Fellows working in restorative practices with the Residential Life team, a group known colloquially as REST, facilitate six-week circles for first-years as they adjust to campus life. These circles allow dorm-mates to share and learn from each other and lay the foundation for other dialogues students will experience across their four years. They prepare students to address instances in which they’ll need to work together to navigate complex conversations, manage conflict, and solve various problems.

Munroe also leads confidential circles or smaller groups when needed. Last spring, after the war in Gaza broke out, student protests erupted across campuses nationwide, including an encampment on Vassar’s Library Lawn. Amid all the turmoil, students at Lathrop House requested a restorative circle. They wanted a space where their dorm could process what was happening on campus and also in Gaza. In a 2024 article introducing the office and expanded EP program, House Events Officer Yaksha Gummadapu ’26 said that the circle worked and helped students release their fears.

Due to the success of these efforts, restorative circles are becoming a part of Vassar’s campus culture. The community not only uses circles to bridge divides on a diverse campus, students increasingly seek out Munroe and her office for a variety of needs. Student groups and athletic teams have come to Munroe to learn how to give and receive constructive criticism. After student Avery Kim ’26 died last spring, the office held circles to help students process the sudden tragedy.

“We’re also training some administrators so that we have more avenues to respond to these moments of interpersonal, political, collective crisis in a meaningful way,” Munroe said.

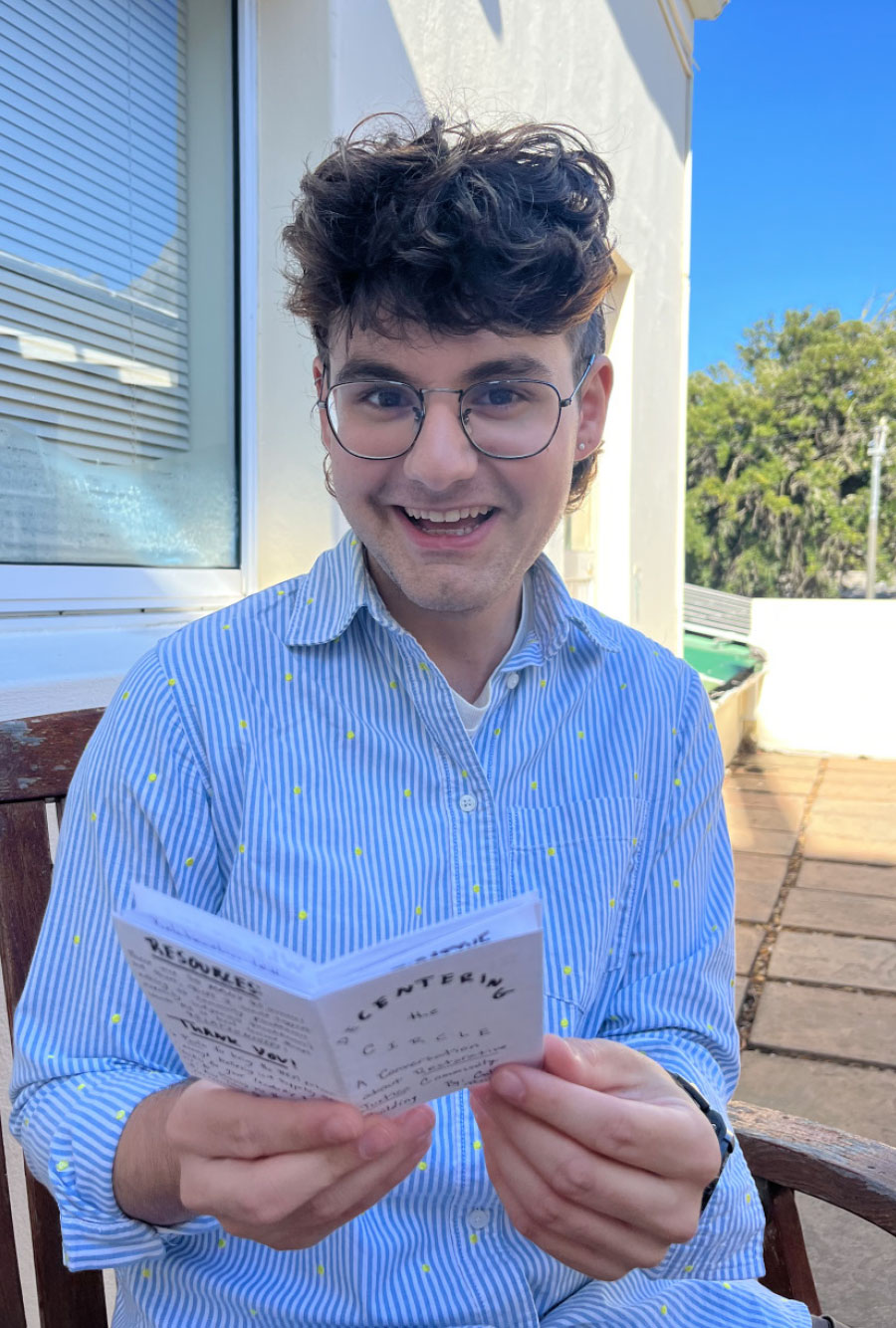

Calder Beasley ’26, who served as Education in Restorative Justice Intern for the Mediation Center of Dutchess County in partnership with the Office of Community-Engaged Learning, created a zine to help new practitioners as part of a final project for a restorative practices class Dean Inoa taught in 2024. The project became a way for Beasley to reflect on what he’d learned as an intern at the Mediation Center and in his juvenile- and restorative-justice courses.

Beasley constructed a reproducible handout using an 8 ½” x 11” sheet of paper and a marker, folding the sheet on itself a few times to create an eight-panel booklet. Each panel provides simple exercises and visuals that instruct readers how to reflect on the kinds of relationships they are building or how to determine the needs of their communities and its individuals.

Courtesy of the subject

Despite the gains the office has made, Munroe knows there’s more work the office can do. “I have a dream of training a bunch of Vassar College administrators so that we have a whole host of skilled facilitators,” Munroe said. She wants to build out the office’s capabilities so that anyone on campus in any capacity can request a restorative process.

Dean Inoa also hopes to find a way to hold restorative justice conferences as a part of student conduct hearings. The conferences would enable dialogue about the harm done by a student’s actions.

Talia Yustein, ’26, who serves on the REST team, notes that “although restorative justice is often focused on a singular relationship, it is really about restoring mutual trust and care within the larger community. As a house team, we are largely responsible for establishing and maintaining a supportive residential environment for all Vassar students. We play a role in community expectations, preventing unsafe situations, and managing conflict.”

Lathrop House Student Fellow Sarah Scarr ’27 said that the use of restorative practices has helped students feel more comfortable discussing alcohol abuse and excessive drinking. “They know that I’m not there to punish them, and the College is not working to punish them, but rather there to help them learn from this experience, to engage in safer practices,” Scarr said.

Moving from restorative justice to transformative justice, Munroe argues, may require moving beyond the circles the campus has become used to; they’re a starting point. The natural progression this framework lays out, she contends, means changing the campus’s mindset and orientation to conflict and community on campus and in the world.

On the student side, Beasley and Scarr want more students to have peer-led, restorative conversations about politics. Beasley, a dorm voting advisor for Vassar Votes, hopes to transform political debates into conversations about the needs and values that local, state, and national elected leaders need to meet.

Scarr also sees an opportunity for student fellows to introduce more political topics into first-year circles. She’s heard feedback from her peers that students want to be able to discuss or debrief political topics and other conversations happening beyond Vassar with their dormmates.

These and other students are inspired to listen to and address needs in the Vassar community and beyond as “a fundamental step toward peacebuilding,” Scarr notes.

“A lot of times, in moments of crisis, it can be really easy to shut down,” Beasley said. “But I’ve learned from restorative justice to focus on what I can do.”