Justice Revisited

Justice Revisited

Overturning

Wrongful

Convictions

©Tina MacIntyre-Yee, Democrat and Chronicle – Part of the USA Today Network

Overturning Wrongful Convictions

From a young age, Grossman, who was born with a mild case of cerebral palsy and has a moderately severe stutter, was always a bit of a maverick, with decidedly liberal politics to boot. That’s one reason he chose Vassar; the school appealed to him for its progressive traditions. “The College started as kind of feminist institution when it wasn’t as common to educate women,” says Grossman. Being a criminal defense attorney, he says, “is the perfect job for someone like me because you’re opposing the government in every case. That appeals to my anarchist instincts.”

Yet despite his penchant for taking on a challenge, Grossman was not optimistic when, in 2018, he got a call from a woman named Deborah Kilbourn, who was volunteering with a church group that helped get people who had been wrongfully convicted out of prison. Kilbourn told him about a man named Michael Rhynes who, in 1986, had been sentenced to 52 years to life in prison for a murder he maintained he had never committed. Kilbourne believed him, and relayed that Rhynes was accused, along with several others, of attempted robbery and the murder of a bar owner and bar patron in Rochester, New York, in 1984, when he was 23 years old. Rhynes, who lived with his mother, said he was at home sleeping at the time; his mother concurred. The defense counsel moved to dismiss the indictment due to conflicting accounts from witnesses and insufficient evidence, and the District Attorney’s office did not oppose the motion.

But the judge denied the request, merely postponing the trial and requesting that prosecutors find more evidence. After an account of the case was published in a local Rochester newspaper, two individuals came forward and said that Rhynes had admitted to them when all three were in prison that he had fired the fatal shots—testimony that led to Rhynes’s conviction and sentence.

That was good news but Rhynes’s release was no shoo-in, or as Grossman says bluntly, “Even with those admissions, it’s tough to get a hearing. One of the f—ked up things about the law—and there are many—is that recantation evidence is often viewed by courts as not credible.” And indeed, one of the informants said that he tried to get in touch with the DA’s office several times to say that he had lied about Rhynes, something he outlined in his affidavit. His calls were never returned.

Grossman’s partner Jonathan Edelstein was slated to represent Rhynes in court, while Grossman wrote up the legal papers. “They were pretty good—good enough to get us a hearing.” With his stutter, Grossman relies even more than most lawyers on an ability to write well—a skill he attributes to his time at Vassar. “In the kind of work I do—appellate work—the most important thing is to be able to write in a persuasive, interesting way to keep law clerks’ and judges’ attention,” says Grossman.

Edelstein and Grossman won the hearing, and Rhynes, who by that time had spent close to 40 years in prison, was released on December 19, 2023, but not all of Grossman’s cases have such happy outcomes. “We’ve probably exonerated between five and eight people over the course of my career,” he says. “Last year, for instance, my partner and I got the judge to agree to reduce the sentence of Frans Sital, who got life without parole when he was 17 and after thirty years inside, he just got out,” says Grossman. “But I’ve also had my fair share of disappointments, including two cases where I believed my clients were innocent—but we lost.”

Still, Grossman has no regrets. “You won’t ever get rich being a criminal defense attorney,” he says. “But I never wanted to make a living by exploiting or profiting off someone else.”

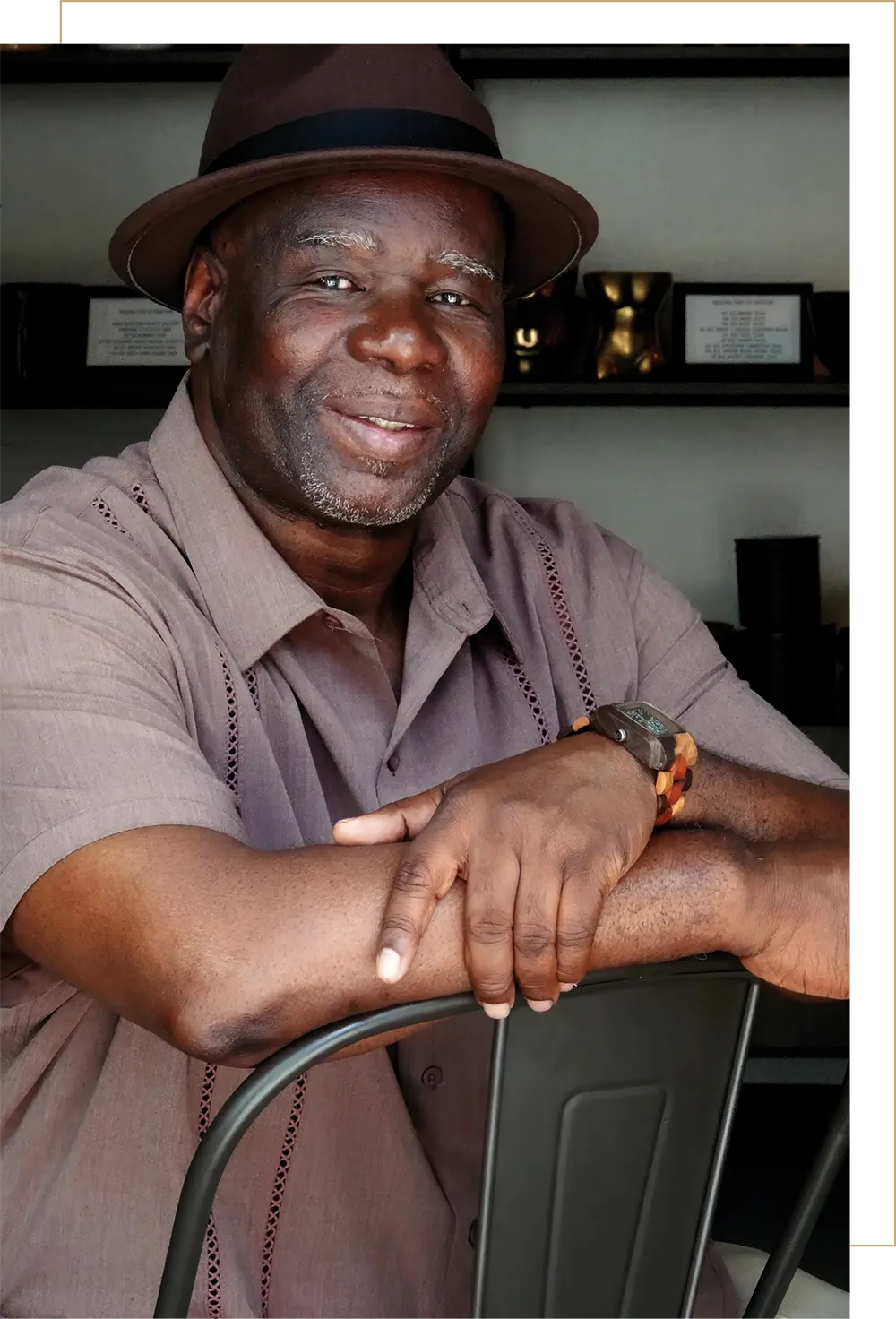

A Free Man:

Michael Rhynes Today

Purple Warriors:

Supporting Domestic

Violence Survivors

Karl Rabe

Purple Warriors: Supporting Domestic Violence Survivors

Others in the community also knew of Addimando’s home situation, including the local police and Child and Family Services, yet when Addimando called 911 to report what had happened, she was arrested, leaving her two young children, then two and four, to be cared for by Addimando’s sister, Michelle Horton. “That’s when the women in Nikki’s life started coming together,” says Freedman. None of us had any knowledge of the legal system, but we had money, resources, and we knew how to do research, make calls, and rally our skill set.” Soon, there were 12 women who, together, formed the Nikki Addimando Defense Committee, including Nicole Bonnelli, director of the Infant Toddler Center on campus. “Three of us were connected to Vassar, then there were a whole bunch of other ‘purple warriors’ in our community,” says Freedman. “Purple is the color of domestic violence awareness, and a lot of my wardrobe is now purple.”

What Freedman didn’t know then is just how powerful that community could be—nor that they would have to fight for seven years for Nicole Addimando’s freedom. “We had people showing up in the courtroom, at rallies and at vigils, including a bus full of Vassar students,” says Freedman.

One of those students was Emma Ratzman ’21, who got involved in the Defense Committee as an intern through Vassar’s Office of Community-Engaged Learning. “I’ve always been interested in the legal system, and I’ve had some personal experience with domestic violence,” says Ratzman, who graduated from Georgetown Law this spring and is now clerking for a family-law judge in Washington, DC. “I was drawn to the opportunity of working with a group of women doing grassroots work and advocating for changes in policy.”

One task Ratzman took on was to figure out how to send care packages that were coming in from people who had heard about Addimando’s case. “I spent weeks reading through the prison regulations—it’s such an opaque system. In the end, we were able to figure it out, but it left me thinking, ‘How in the world would someone without these resources navigate this!’” says Ratzman.

That result caused an uproar that rippled out into the community and beyond. “Nikki was one of the first people in New York to be tried under this new law, but even with all the evidence, she wasn’t eligible to be resentenced. If she wasn’t eligible, who would be?” asks Freedman.

Newly determined, and with the support of some state legislators and the weight of domestic violence groups like Sanctuary for Families behind them, the Defense Committee secured the professional representation of Garrard Beeney from the law firm Sullivan & Cromwell LLP. “He was the most compassionate human being, and he argued Nikki’s case before the state Supreme Court’s Appellate Division, where only 5 percent cases that are requested to be heard are accepted,” says Freedman. The ruling: That the way the courts had handled Addimando’s case was “antiquated.”

Addimando was given a new sentence of seven and a half years, including time served, and the Defense Committee was there for every day, week, and month of it, not only helping Addimando, but raising funds for her sister, Michelle Horton, who had quit her job as a journalist to care for her young niece and nephew, (Horton’s book about the experience, Dear Sister: A Memoir of Secrets, Survival, and Unbreakable Bonds, was released in January 2024.)

“This group of beautiful, passionate, dedicated people came together and we formed a deep bond,” says Freedman, who was at Bedford Hills Correctional Facility along with the rest of the Defense Committee on January 4, 2024, when Addimando was released. “It was one of the best days of my life, to see her walk out into the arms of her family,” says Freedman.

Meanwhile, along with her day job, Freedman is keeping up the fight for survivors of domestic violence. “Because the appeal was successful, this case is now being used as a precedent to free other women in New York State,” says Freedman. “And a bill similar to the DVSJA in New York was recently passed in Oklahoma, so there’s hope that things are moving in the right direction.”

For that, she thanks the community of people she found at Vassar and beyond. “Part of what drew me to work here is that the College lives by its values and has a strong social justice orientation, all of which inspired me to learn more about systemic oppression,” says Freedman. “I’ve also learned that progress is only made through working together and shared action—and I’m so grateful for my friends, colleagues, and Vassar students who have helped me find my place and voice in this fight.”

Fighting Racial Bias

and Adult Sentencing

For Juveniles

Fighting Racial Bias and Adult Sentencing For Juveniles

Those values were reinforced when Murphy got to Vassar, he says. “The school attracts people who want to make a career out of humanity—and what you learn there reinforces that desire, not just philosophically but by giving you the analytical skills that justice work requires.” He points to what for him was a life-changing course called Prisoner and Imprisonment taught by now Dean of the College Carlos Alamo-Pastrana, a professor of sociology. “Thirteen years before George Floyd was murdered, we were asking profound questions about the disconnect between prisons and public safety, the disconnect between legal doctrine and morality,” says Murphy. “I’ll always be grateful for that class, which created a framework for thinking about these important questions and providing the space to both challenge and articulate our beliefs.”

Murphy has been living those beliefs since he graduated from Vassar and took a job at the Office of the Appellate Defender in New York City, where he worked on appeals cases as a client advocate and investigator. After graduating from NYU Law School, Murphy worked as a lawyer with the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, AL, representing people on death row, advocating for juveniles who had been sentenced to die in prison, and supporting the re-entry process.

Now at the NAACP LDF for two and a half years, his work there can be described as extremely challenging, but he finds it satisfying to represent people sentenced to death or life without parole, including people who were children at the time of their arrest.

Murphy also submits briefs in significant constitutional cases, urging courts to eliminate the pernicious influence of racial bias in the criminal legal system—often related to issues of qualified immunity, jury discrimination, and sentencing. He presented oral argument last year before the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court in support of a person whose lawyer directed anti-Black and anti-Muslim sentiment toward him and on social media. “The court found that defense counsel’s racial and religious animus constituted a structural error, and all 18 of this man’s convictions were overturned,” says Murphy. “The case also opens the door for dozens of people to have their convictions and sentences vacated and provides persuasive authority for other states to approach similar cases in similar ways.”

Another case of which he is particularly proud resulted in the release of a 17-year-old client who had been sentenced to life without parole. “The judge had told him, ‘You are going to die in prison.’” Because of Murphy and his colleagues at LDF, he didn’t.

In 2012, the Supreme Court held in Miller v. Alabama that children are constitutionally different for purposes of sentencing. Based on that ruling, Murphy’s client was resentenced and made eligible for parole. “Except this was in a state where the parole board was not releasing anybody,” he says. Murphy got to work putting together evidence of his client’s progress in prison and his life circumstances—what’s known as “mitigation work,” which considers factors that argue in favor of a person’s release or lesser sentence, such as remorse. “We presented our case [at] the parole hearing, and after a lot of initial resistance, the board released him,” recounts Murphy. His client is now thriving, working as a certified cook at a homeless shelter. “He wanted to give back,” says Murphy, “and it’s amazing to see him live such a beautiful and vibrant life in the world outside the walls.”

Last April, in his personal capacity, Murphy spent a weekend in New York with another former client, a man who was imprisoned for 52 years and denied parole 14 times. “We started working together during my first year of law school, through a volunteer organization called Parole Prep, which helps incarcerated people prepare for their parole hearings,” says Murphy. “After decades of denials and despair, watching him walk out of prison was the most incredible feeling. It’s a memory I keep tucked away for the more challenging days.”